Was Mannerism an Art Movement During the Age of the Enlightenment?

- the thematic guide to France

Fine art in France - : 1590 - 1790

From classical baroque to French rococo

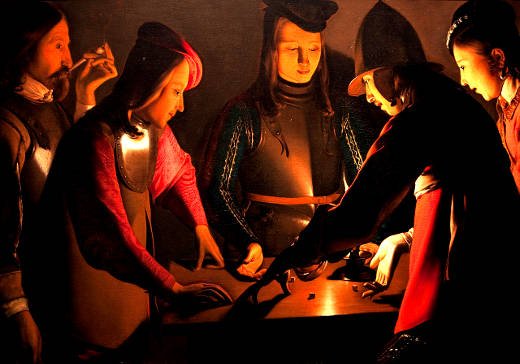

George de Latour - Dice players - Preston Hall museum - Stockton

By the end of the 16th century, the French Renaissance was coming to an end as writers, thinkers, artists and architects moved on to explore new horizons. Equally with the Renaissance, the new directions in French art were inspired initially by what was going on in Italian republic. Here, innovative artists had long since moved on from the naturalism of High Renaissance art, starting time into a more exaggerated style known as Mannerism, every bit exemplified in the works of Bronzino or Tintoretto, and so, by the end of the 16th century to a new type of effusive classicism which afterwards on became known as "bizarre fine art"

Baroque was not a break from Renaissance classicism, it was a evolution. At the time, artists and architects whom we today think of every bit beingness the masters of Italian baroque art saw themselves equally painting and working in a new phase of classicism, one that emphasised emotions, anticipation, movement and vitality. Baroque was a new classicism exaggerated past intense light and shadow, dramatic perspecitves, and a sometimes exuberant use of color.

Seeing baroque fine art as a permutation of classicism sometimes requires a bound of faith when one looks at the works of nifty baroque artists of Italy, Flanders or Spain - such as Caravaggio, Rubens or Zurbarán. By dissimilarity, much of French baroque is altogether more clearly classical, with less of the effusion seen in other parts of Europe, remaining more "classic" and subdued in its development of the idiom of Renaissance art.

The adjective "Baroque" fifty-fifty seems misplaced when used to describe the works of some of the greatest French artists of the seventeenth century, notably Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin; only it sits well with 2 of import artists who were contemporaries of Caravaggio, George de Latour and Philippe de Champaigne.

Sometime called "the French Caravaggio", Latour (1593-1652) who came from Lorraine, specialised in paintings, mostly small-scale canvasses showing intimate candle-lit scenes with intense light and shade. By dissimilarity, Philippe de Champaigne, built-in in Brussels in 1602, worked for near of his life in Paris, where he was called upon to pigment many big religious paintings equally well as portraits including several of Cardinal Mazarin. His paintings on religious subjects, especially when relating to expiry show all the intensity of emotion that tends to characterise baroque art.

Nicolas Poussin - The Holy Family with Saint Elizabeth & John

the Baptist - Leningrad - the Hermitage

Among the French artists of the starting time half of the 17th century, the one with whose works the word baroque is quite easily associated was Nicolas Poussin. Born in Normandy in 1593, Poussin came every bit a young artist to Paris where he worked for a few years earlier moving to Rome in 1624, and staying there for most of the rest of his life. He was a fairly prolific painter, taking his inspiration from bang-up religious and classical themes, which he interpreted in a grand still intimate style, less effuse than the works of his great Italian contemporaries, less removed from the style of the High Renaissance.

Poussin evolved his own theories of painting, notably his idea of the grande manière, the view that a work of art must narrate a story in the clearest possible manner, without disruptive the issue with besides much distracting detail. In this style, his fine art distinguishes itself from mainstream baroque art in which a profusion of detail often distracts singularly from the main theme.

Poussin's contemporary, Claude Lorrain (1600-1682), was a very different kind of artist, and 1 whose works were to inspire a whole post-obit of neoclassical painters. For the record, it is useful to realise that Claude Lorrain goes under several different names: born in 1600 in Lorraine, and known from birth as Claude Gellée, he became known in the art world equally justClaude, or Claude le Lorrain (Claude from Lorraine). In French he is often referred to equallyLe Lorrain.

Claude Lorrain - Pastoral scene with classical ruins. Grenoble - Musée des Beaux Arts

Similar Poussin, Claude Lorrain spent most of his life working in Rome, where he specialised in imaginary scenes from classical mythology and history. In a sense he was the first great French mural painter, taking the landscape chemical element out of the background where information technology had been a major but secondary chemical element in the works of many Renaissance artists, and making information technology into the dominant chemical element of the painting. Lorrain's paintings thus break from tradition by being not depictions of people or events in an incidental landscape, but paintings of landscapes or seascapes that serve as a setting for the idealised depiction of an incidental story or issue taken from the biblical repertoire or from classical mythology. Lorrain'due south about mystical depiction of idealised classical Italian landscapes was to inspire many artists not just in France - such as Horace Vernet or Hubert Robert - but also in England and other parts of Europe for the next hundred and fifty years

With the two greatest French artists of their time working in Rome, patrons in French republic looking for portraits or works of art for churches, chapels and châteaux used the services of a large number of less remembered artists, painting often with considerable skill simply as followers, rather than innovators, in the field of art. Two names stand up out from the residual, Charles Le Brun and Hyacinthe Rigaud.

Charles Le Brun (1619 - 1690), who studied in Rome nether Poussin, was considered by Male monarch Louis Xiv to be the greatest French painter of all time, and was commissioned by him for awe-inspiring works and ceilings in his palaces at the Louvre and Versailles. Le Brun also worked for other patrons on projects in various châteaux, such as Vaux le Vicomte, where his works can nevertheless exist seen today.

Le Brun was also one of the key movers in the struggle to get official recognition for the best artists in France, an idea that somewhen led King Louis Fourteen to ready, in January 1848, the starting time French Imperial Academy of painting and sculpture. From then on, the land'south greatest artists would get official acknowledgement, making the Academy the official czar of good fine art.

Hyacinthe Rigaud (1659 - 1743) was the great portrait painter of the Grand Siècle, and the portraits he painted during the 2nd half of the 17th century have determined the style that people see or imagine the great and the famous who gravitated effectually the Dominicus Male monarch during this flow of absolutist monarchy in French republic.

The influence of Louis XIV on art in his age cannot be underestimated. If the 2nd part of the 17th century was not a cracking catamenia of innovation in French fine art, this was in no small degree due to the office played by the Male monarch and his courtroom equally arbiters of fashion, style and fine art. Artists who wished to brand their way in life knew that to do so they had to follow in the path of Le Brun or Rigaud, painting portraits for the wealthy and decorating their houses and churches with suitably ornate canvasses and murals in the style of the age. It was not until the commencement of the 18th century that things began to change.

The harbinger of change was Antoine Watteau (1684 - 1721). Born in Valenciennes, a town on the border with Flanders, Watteau start found work equally an artist in Paris painting copies of Flemish genre paintings for bourgeois customers. Later he became a genre painter in his own right, specialising in theatrical scenes. His depictions of staged rural scenes are very unlike from the rural scenes painted by Claude Lorrain; and while the landscape chemical element is remains important in Watteau'south work, information technology is the people who are the main subject. With Watteau, French art began the movement from the grandeur of bizarre art towards the smaller-scale and more intimate fashion known as rococo.

A gimmicky of Watteau, and another genre painter though not at all in the same genre, was Jean Siméon Chardin (1699 - 1779). Chardin was strongly influenced by Dutch genre painting which had become pop throughout Europe, as the new eye classes and expanding aristocracy sought and commissioned works of art to decorate their houses. Chardin'southward art is neither baroque nor rococo nor classical; it echoes the work of painters similar Vermeer or Pieter de Hooch, taking its inspiration from northern Europe, not Italy, from everyday life and ordinary people, not from great moments in history, faith or mythology. Chardin painted still life scenes, domestic scenes and portraits of ordinary people, and in doing so helped to move French fine art in a new management that was to inspire many French artists for over a century. Both Manet and Cézanne recognised the influence of Chardin on their ain art.

Nevertheless while French art, with Chardin, was moving into new territory beyond the influence of the baroque, other artists were following Watteau; foremost among these was these Paris-born artist François Boucher (1703 - 1770) who even in his fourth dimension was recognised every bit the main of rococo art.

A prolific artist, Boucher was both painter and engraver, as well as a designer of tapestries. After being admitted to the French Royal Academy in 1731, he was much in demand as a portrait painter, and received numerous commissions from Regal and aristocratic patrons, almost notably from Madame de Pompadour of whom he painted a number of portraits.

Boucher painted in a style less delicate than Watteau, and his work is much more than thematically diverse. He painted genre scenes, portraits, religious paintings, classical scenes and even chinoiseries, introducing into French art a new sensuality that owes something both to Rubens and Tiepolo. While his portraits of Madame de Pompadour, Louis 15's favourite mistress, are fully clothed, Boucher excelled in nudes variously portrayed every bit Venus, Diana or other mythological beauties.

His assuming utilise of color - far less discreet than Watteau - was an inspiration to many younger artists but displeased the showtime great French art critic, Diderot, who wrote of one of his paintings on show at the 1763 Salon : "This man is the ruin of all young aspiring painters. Inappreciably do they know how to hold a castor and a palette than they are torturing themselves with garlands of children, painting podgy vermillion backsides, and throwing themselves into all style of extravagances that are non compensated for by warmth, nor by originality, nor by kindness, nor by the magic of their model: they just imitate his mistakes."

While Diderot was critical of Boucher partly on moral grounds, he enthused nearly some other younger painter, Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1725 - 1805). Greuze came to popularity as a genre painter in the way of Chardin, specialising in sentimental portraits and scenes with a moral, which went down well with Diderot and were well in keeping with the spirit of the age.

Greuze'southward moralizing scenes, with their stylized poses and classic movements, besides prefigure the great heroic works of the upwardly and coming generation of neoclassicists, notably David and Gérard, who would accept moralising art onto a new plane, out of the intimacy of the family scene and small genre painting, and onto the vast canvases of the Imperial age that was soon to dawn

By the 1770s still, Greuze had fallen out with the University, and became something of an independent painter and engraver, popular with the people, no longer with the establishment – a popularity that doubtless helped him to come through the French Revolution unscathed.

Classic tardily rococo : the Swing, by Fragonard - 1767.

London - the Wallace collection

And so finally to the last great artist of the pre-Revolutionary age, and the last great exponent of French Rococo fine art, Honoré Fragonard (1732 - 1806). After studying for a short catamenia with Chardin, Fragonard went on to work in the studio of Boucher, with whom he felt considerable empathy - to such a point that Boucher allowed him to re-create his own works.

After a menstruation when he worked essentially on history paintings, interpreted with the lightness of his rococo bear upon, Fragonard afterward became known – and is today essentially remembered – equally the painter of frivolity, painting scenes of the aristocracy at leasure in idealised gardens or parkland, or at home with their children. As such he was in much demand as long as the aristocracy continued to enjoy their privileged lifestyle; but that was not to be for long.

Past 1785, rococo equally a genre had run its grade, and aware France was heading for the dramatic events of 1789 which would profoundly touch not only the fashion the country was organised, but about averything well-nigh French life and civilization likewise. While revolutionary France would take a place for celebrated art, for some forms of genre art, and for fine art with a moral, it would accept no place for the frivolity of rococo, and then intimately linked to the lifestyles and tastes of the Ancien Government. And though Fragonard as a man survived the Revolution, Fragonard the creative person did non. It would be a generation or more than before whatsoever later on French artists would recognise whatever kind of historic debt to Watteau, Boucher or Fragonard.

The About-French republic.com history of art in French republic :

- Art and architecture in Medieval France

- French art in the Renaissance

- French art from Bizarre to Rococo - 1590 - 1790

- Neoclassicism and Romanticism

- Naturalism and realism - landscape and life in 19th century French fine art

- Impressionism

- Mail service- Impressionism - from Pointillism to Cubism

Website copyright © About-French republic.com 2003 - 2021

Photos: all photos on this page are in the public domain.

Source: https://about-france.com/art/baroque-to-rococo.htm

0 Response to "Was Mannerism an Art Movement During the Age of the Enlightenment?"

Post a Comment